To this day, many on the Eastern Seaboard consider the commissioning of painted portraits to be simply a matter of tradition and culture. Inherited from Europe and Britain during colonial times, portraits were, for over a century, their most common means of indicating a person’s status and place in history. And now, even with the technology that is available for creating immediate imagery, the painted portrait on the East Coast continues to be a symbol of distinction.

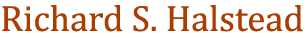

Chicago, on the other hand, was founded as recently as 1833, less than thirty years before the Civil War (1861–1865). Although the Civil War stimulated the city’s growth and economy, it stunted its cultural development. Then, only seven years after the end of the war, Chicago was devastated by fire and had to completely rebuild itself, delaying its cultural development even further. By that time, photography had become an art form in its own right and a reasonably efficient way of documenting a person’s physical character. Efficiency was a key word for the fast-growing new city. Portrait painting, to the Midwesterner’s pragmatic, bottom-line view of life and business, was an inefficient, nonessential item—even for luxurious living. Consequently, today the second largest city in the United States and a national hub of business can only lay claim to a scattering of early portraits and, in general, those are of a mediocre quality. Furthermore, Chicago’s social and financial elite have not typically thought of portraits as being a connection to their ancestors or to their progeny and future generations.

There have been some exceptions, however. One of the earliest portrait artists of real quality to live and work in Chicago was George Peter Healy. Originally from Boston, Healy was classically trained in Paris by two of the most celebrated artists of that time, Thomas Couture and Antoine-Jean Gros. He became so admired as an artist in France that he was commissioned to paint King Louis Philippe. Following that the King then commissioned him to paint portraits of the most important leaders in the United States, which brought him back to his native country. That led to a long succession of solid, insightful portraits of many of America’s presidents, statesmen, business leaders, and contributors to the country’s arts and letters.

Healy came to Chicago in 1855 and painted portraits of Illinois’ most influential figures until he left in 1869. He was in Springfield to paint Abraham Lincoln shortly after Lincoln had won the the Republican Party’s presidential nomination. Healy found Lincoln to be an especially entertaining, convivial sitter, laughing at his own stories and making the time pass rapidly. At one point during the sittings Lincoln was going through some letters and he began to laugh. He read to Healy the letter, which was from a young girl who wrote that he would look better and would have a better chance at winning the presidency if he were to grow a beard. Lincoln asked Healy if he would like to paint him with a beard, to which Healy responded, “No.” The resulting portrait in fact presents the future president in a way that is very different from the iconic, bearded image that we now associate with him. It is more youthful, more open, and, I think, more revealing of the essential person than we see in any of the other portraits of him before or after that.

Presidential hopeful, Abraham Lincoln, by George Peter Alexander Healy

After the Civil War, while Healy was again in Europe, Congress commissioned him to paint a posthumous portrait of Lincoln. The figure was based on a painting Healy had previously made of Lincoln conferring with Generals Sherman and Grant and Admiral Porter. In the portrait Lincoln is represented in a thoughtful, attentive pose, leaning forward with his bearded chin resting against his hand. With this painting, Healy finally had an opportunity to paint the president as Lincoln’s young admirer had suggested.

In 1892, after more than two decades of painting continuously in Europe, Healy returned to Chicago—quite possibly to contribute to the Columbian World Exposition—and died in Chicago a few years later.

One of the greatest “direct,” bravura style painters of all time, Anders Zorn, came to Chicago to participate in the Exposition in 1893 and immediately took a liking to the city and its people. Despite his immense talent, international acclaim, and his marriage to a wealthy society woman, Zorn had received a rather haughty reception from the upper classes in Europe. According to Zorn, they behaved with “ceremonious style and artificial customs” that he never felt comfortable with (from “Saint-Gaudens, Zorn and the Goddesslike Miss Anderson” by William E. Hagans). Chicagoans, on the other hand, responded more to the quality of his work and character than to his pedigree, which was of a Swedish peasant stock. The simple, warm welcome Zorn received from Chicagoans was heartening to him and was confirmation of what he had come to feel in general about Americans. According to biographer William E. Hagans, Zorn wrote the following in his memoir: “Over there [in America], when they say ‘He’s all-right,’ all doors open to the foreigner, which Europeans cannot understand. Openness, honesty, straightforwardness, punctuality, these things are included in the testimonial ‘He’s all-right.’”

Naturally then, Zorn stayed in Chicago for a while. During his stay, he painted some outstanding portraits of Chicago’s industrial, commercial, and political leaders, such as Charles Deering (in the collection of the University Club), son of the founder and CEO of International Harvester, and department store magnate Potter Palmer and his wife. He also painted the chief architect of the Exposition, Daniel Burnham, and two U.S. senators from Illinois.

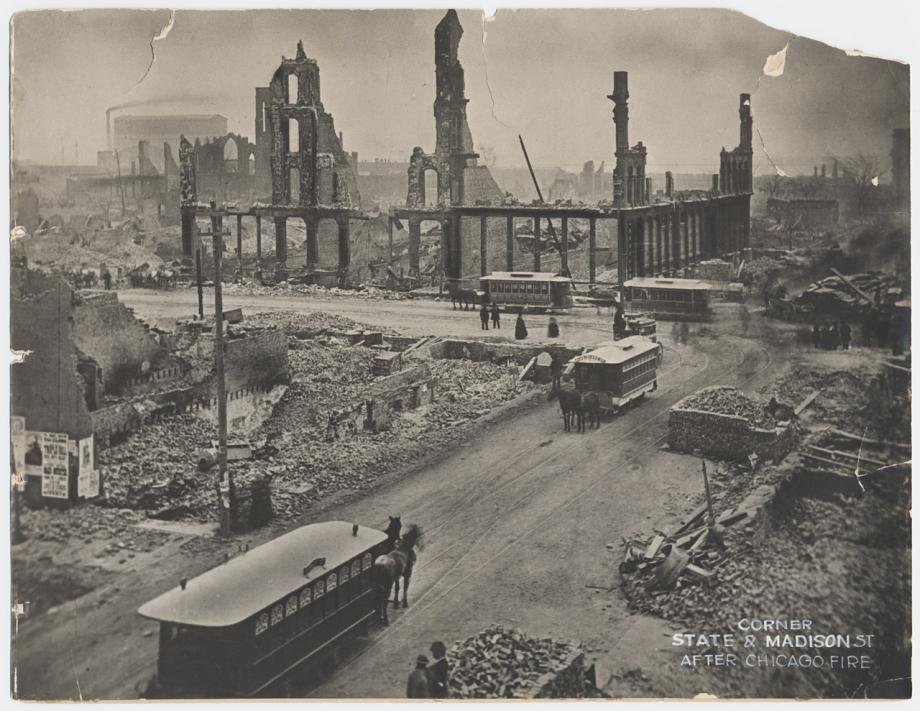

President Abraham Lincoln by Augustus Saint-Gaudens

The sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who was a friend of Zorn’s and also came to Chicago because of the Exposition, left some truly great portrait sculptures here as well. His full-figure sculptural portrait of Lincoln in Lincoln Park is one of his most impressive pieces and certainly one of the finest and the strongest, symbolic portrayals of President Lincoln and the principals he now represents.

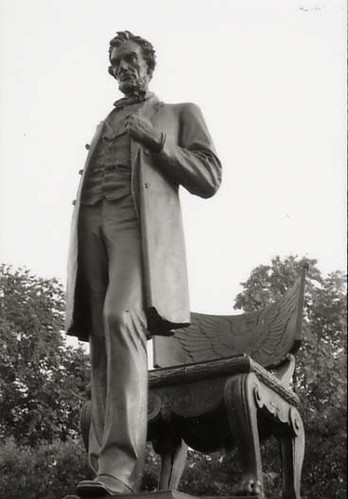

Justice John Paul Stevens, U.S. Supreme Court, by Jim Ingwerson

Since the 1960s, James Ingwerson has been the most prominent of all the Chicago portrait painters. There have been other portraitists of quality, but during his long career, Ingwerson has consistently stood at the summit.

Ingwerson’s quiet, unassuming manner belies the solidity and confidence that can be seen in his paintings. Looking at one of Ingwerson’s portraits, one is immediately struck by the perfect balance between the painting’s quality and the quality of the person portrayed. They are painted with a skill and a grace of execution that seems effortless, yet above all else there is great dignity in his creative expression, reflecting the character of the artist as well as that of his subjects.

In addition to subjects across the country, Ingwerson has painted many of the most influential Chicagoans of the past half century, and I am convinced that his portrayals of them will survive far beyond anyone’s memories of the people, just as Healy’s and Zorn’s will.

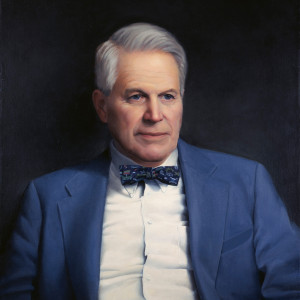

John Baird, CEO and Chairman, Baird & Warner, by Richard Halstead

Realism in general has had a difficult time reestablishing its acceptance in Chicago, however. After the 1940s, Chicago’s elite,feeling somewhat provincial in comparison with their eastern cousins, embraced the latest and often iconoclastic fashions in art. Not until recent years have tastes here become more eclectic and, as a result, have traditional art and portrait painting been given a fresh evaluation. Now, at long last, painted portraits are not competing with photography as they did in the past but, instead, generally live side-by-side as separate entities. There also seems to be an easier relationship between the traditional and contemporary arts, the two sometimes mixing in the same environment.

I believe we, here in Chicago, are about to enter an interesting period for portrait art. I sense that it is reemerging as a new tradition—not as an imitation of a past tradition or as an appropriation of other cultures’ customs, nor even as a self-conscious reaction to either of those. I believe a new tradition for portrait painting is emerging as something fresh, original, and distinctly ours, a tradition that specifically represents the values and life today in Chicago and the Midwest.