by Richard | Sep 3, 2013 | Portrait Artists

The Wyndham Sisters by John Singer Sargent

Considering how many books and articles have been devoted to John Singer Sargent’s life and paintings, there is surprisingly little written that attempts to explain the phenomenon of his paintings. Even artists who emulate his style generally see them as the works of a transcendent mind that can never be understood through analyses. For many of the students and followers of Sargent, the spontaneity within his paintings is the essence of that transcendent mind. Consequently, the principle they tend to apply when viewing his work, or in making their own paintings, is “Don’t think too much.”

He did fill his paintings with spontaneous passages, as a jazz musician might, and after a brief time early in his career it seems that he went directly into his paintings without any significant compositional studies. Nevertheless, there is a conscious mind behind those flashes of genius, judging, selecting and organizing them into a cohesive whole. Sargent was said to have frequently scraped down, rubbed out and reworked various areas to get the effects that he wanted. The combination of letting things fall as they may and of reconsidering or editing from those moments is what made his paintings great works of art.

Sargent had a special advantage over other artists in that he could think at an extraordinary speed. That may seem like an insignificant detail, but in a direct painting style an artist has to make important decisions within the limited time he has before the paint dries, just as a musician’s mind has to work at the speed or tempo of the piece he is performing. Sargent had a quick and agile mind, and one that could think throughout that drying time toward a final and complete orchestration.

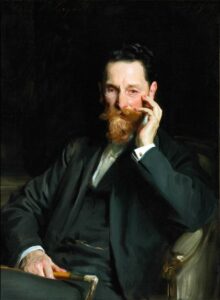

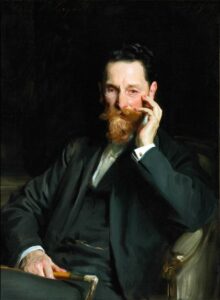

Portrait of Joseph Pulitzer by John Singer Sargent

To have a basic understanding of Sargent’s creative process, a person needs to consider what Sargent was not. He was not an artist consumed with interest in the subject’s character, so he was not distracted by it. While he was painting a portrait of the publisher Joseph Pulitzer, he actually stated that he was not interested in character, saying, “Sometimes I get a good likeness—so much the better for both of us. Sometimes I don’t—so much the worse for the subject, but I make no attempt to represent anything but what the outward appearance of a man or woman indicates.”

He was more interested in the ballet of the figures moving about in the illusionary worlds he created on canvases and in the visual music of his compositions and brushwork. Essentially, he was consumed by the creation of beauty, and he seems to have had no need to “say” anything beyond that. His clients must have sensed this fact even if they didn’t understand it. In their day, his portraits were recognized as elegantly modern images in which people wanted their likenesses placed, even if that likeness was vague.

I believe the best way to understand Sargent’s work is to see in his paintings parallels to music. Music is a timeline form of art (art that moves in time) in which the lyrics, if they are used, are carried by the rhythm, melody and spacing of time within it. Painting is a static form of art, but we view it in a timeline manner, according to where and in what priority our attention lands in different parts of the composition and pictorial space. In a good painting, our attention is guided by principles very much like the rhythm, melody and spacing in music. All representational or realistic paintings, if they are successful, are carried by these elements, described generally as design or composition, or as an underlying abstraction.

The realism in these paintings can be equated to the lyrics in a song in that both refer to ideas (often described as programmatic in music). In representational art, as in music with lyrics, there is always a balance between a reference to ideas, or meaning, and the composition or design that carries that meaning. Generally, however, one side of the equation is more dominant than the other.

In Sargent’s paintings, the realism is of an extremely high order, but the design (the shapes, texture, color, brushwork, form, and movement) predominates in the way it carries that realism. Music lovers talk about being swept away by a particular piece of music and that is very much like what happens to those of us who love Sargent’s work. The abstract side of his paintings moves us with the conspicuous excitement and grace of his execution and the unique patterns of his compositions.

But even with that predominance of abstract design, the realism is strengthened by it because it contributes largely to the feeling of life and liveliness of the figures. Sargent’s paintings are grounded in traditional realism, as dancers in a performance are grounded by the stage beneath them, reminding us that they are real people. Sargent’s paintings are firmly planted in the here and now, but the beauty of his performance, as with ballet or opera, is what moves us and elevates us out of the stresses of our daily routines.

So I was not surprised when I learned that Sargent was an accomplished musician as well as a painter. Percy Grainger and Gabriel Fauré, famous musicians and close friends of Sargent’s, said of him that his musical ability was as great as his painting skills. It is apparent, therefore, that either music had a profound influence on the way he painted and the way he thought about painting, or, music and painting were just two aspects of the same thing for him. I’m inclined to believe the latter.

My friend, the French-horn player Lisa Taylor, wrote to me recently describing Sargent’s paintings as having, “a richness, joy, lyricism and mastery of rapturous melodic line and harmony.” She compared them to compositions by the musical impressionists Fauré, Ravel, and Debussy and to the works of Shubert, Dvorak, Mozart, and Brahms, whose compositions she described as “sound tapestries of different textures and colors, created by composers who brought out the best of each instrument for which they composed.”

Others have compared his work to jazz greats. Gerald Lazare, an artist friend and honorary member of the Duke Ellington Society of Canada, sees parallels between Sargent’s paintings and Ellington’s compositions, which combine the improvisations of jazz with formal composition. He compares the dramatic range of extreme lights to extreme darks in Sargent’s paintings with Ellington’s way of using a range of sounds from the highest clarinet to the lowest baritone sax.

Paul Helleu Sketching with His Wife by John Singer Sargent

People often compare Sargent to the artists Velasquez and Franz Hals because of the looseness and dash of their brushstrokes. The brushwork of these great artists, each in its way, is powerful and timeless in its expression, but neither artist’s work has the flowing musical quality that exists in Sargent’s paintings. I associate him more with painters of the late Renaissance and Baroque periods in Italy, especially those in Venice, which was once known as the Republic of Music. The paintings of Veronese, for example, are composed as if they are rolling with elegant song and celebration; Guardi’s brushstrokes are like clear, decisive rings from brass and reed; Tiepolo’s paintings are grand opera at its best; and Tintoretto’s have the energy and intensity of some of the symphonic music of the Romantic period.

To see the musicality in Sargent’s paintings is to expand our experience of them and to understand ourselves better in the course of doing that. The first reaction most of us have to his work is awe. We feel a vicarious thrill in the power and assuredness of his athletic prowess as an artist. Then the music reaches us, independent of the performer and composer, and a door to pure exaltation opens to us. We become aware of that combination of classical order and pure, innocent joy. Many years ago, I saw on the back of an LP album cover a description of the Venetian composer Vivaldi that read, “Entirely serious in his joyfulness.” Could there possibly be a better tribute to the art and creative life of John Singer Sargent?

by Richard | Dec 5, 2012 | The Tradition of Portrait Painting, Unveilings

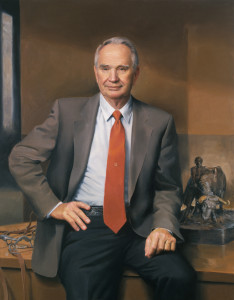

There are lots of organizations out there that have portraits painted, but this [Saddle and Sirloin Club] is one of the few in the country that has portraits painted as a part of their regular tradition for honoring the best and finest of their people.

Not everyone understands this, or the importance of portraits, or, in fact, the importance of tradition. Really we could just put our most honored people on a list that documents their contributions and we could put that up online with a visual documentation from a camera. That would certainly be efficient and economical.

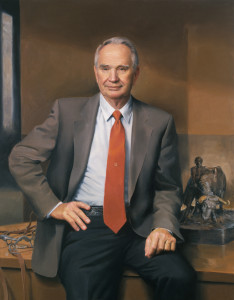

Portrait of Dr. Bob Totosek, Head of Animal Science Dept., School of Agriculture, Oklahoma State University

But a portrait, hand painted with brushes and colors mixed in the oil of flax seed, as portraits were centuries ago, and the thoughtful ritual of one’s peers unveiling that portrait, speaks of the unbroken connection that exists between people of outstanding ability and character from the past, with those of a similar kind in the present and those yet to come in the future.

That gives us a sense of timelessness I think, a kind of reassurance that something, our standards maybe, is not altered by the passing of time.

—Richard Halstead, from November 11, 2012 Speech at the Saddle and Sirloin Club

Click on this link to be taken to the Saddle and Sirloin Club website where you can obtain a PDF of the Saddle and Sirloin Portrait Catalog.

by Richard | Aug 19, 2012 | Composition, Portrait Artists

Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross, Thomas Eakins

In the April 1999 issue of American Artist magazine the contemporary realist painter Jack Beal is quoted as saying about his commissioned portraits, “I tell my clients that when my portrait of them is finished, they will hate it—and their spouse will hate it even more. I capture more truth in a painting than anyone wants me to reveal, and that’s not necessarily flattering.” He also implies that his portraits’ power to disturb his clients qualifies them as museum-worthy, saying, “I warn my clients they will likely put the finished painting out of view for a while and eventually give it to a museum.”

Walt Whitman made a comparable statement about the nineteenth century artist Thomas Eakins when he said, “I never knew but one artist, and that’s Tom Eakins, who could resist the temptation to see what they thought ought to [be] rather than what is.” Eakins was like Beal in that he insisted on faithfulness to the truths before him, but beyond that the two artists are very different.

Although Eakins was ambitious to immortalize himself through his work, and was probably more concerned about his personal aesthetics than he was about people, his portraits never put his subjects beneath him. In fact his paintings often mirror and sometimes parallel the qualities of the people he painted. His portrait of the famous pioneering surgeon Dr. Samuel Gross is a remarkable example of that because it is an obvious, and I think successful, effort to put himself on equal footing with Gross—without diminishing Gross’s stature in any way.

Good composition in a portrait generally indicates an artist’s respect for his subject, or at least of what that person represents, because the solidity and grace it imparts suggests that comparable traits exist within the subject’s character. In light of that fact, the contrast between these two artists becomes even more apparent.

In the article mentioned above, “Jack Beal’s Portraits of Life,” the author Stephen Doherty emphasizes Beal’s interest in composition: “Beal frequently lectures and writes about composition, constantly urging artists to create the illusion of greater and livelier space within their pictures.” Beal’s early paintings sometimes had a rhythmic flow within the figures themselves but his later commissioned works, even within the figures, have none of that movement. Rather than creating the “lively space” he describes in his lectures, his pictures are often static, the shapes are sometimes repetitive and the compositions in general lack a prioritizing of the order in which the viewer’s attention is held. That is tantamount to not composing at all. Compare his composition in the portrait of President Olin C. Robison that hangs in the Middlebury College in Vermont with Eakins’s painting of Dr. Samuel D. Gross, painted for the Gross Clinic and now hanging in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

[NOTE: To see Beal’s portrait, go to www.jackbeal.net/89_robison.html ; copyright prohibits us from making the image available here]

Eakins’s painting of Dr. Gross is built like a grand temple, a tribute to science and to the virtues of thought and accomplishment. It is architecturally solid and within that structure is a carefully choreographed scene. The combination of shapes and the lighting and shadows provide the same order of succession that dialogue and movement create in a masterful stage production. Eakins does not restrict our movements. Instead he gives us logical and inviting options. He allows us to travel throughout his illusionary space along any of many pathways, each one prescribed to give us the fullness of his experience of the scene. He imagines that each of us would enter the pictorial space from a different place with different initial interests and gives us the added option of changing course as our pathway crosses others, but he brings us all to the same ultimate conclusion or completion once we have absorbed the entire picture. None of the routes we might choose are boring. There is no redundancy in shapes or in emotional content. Each figure, including the patient and the students in the gallery, is playing a unique role with a different, very expressive gesture that is an integral part of the whole.

The scene Eakins created, and still creates, has stillness yet moves and has power. We feel a momentary hesitation between events, as if Dr. Gross has deliberately paused in his address to punctuate his last statement or to gain the audience’s full attention before his next point. Even the mood is a careful balance of various elements in the room.

Every small section in this pictorial space is accounted for. There is nothing extraneous. Nothing is overstated or understated. Eakins’s creation is a compositional masterpiece. It is an ideal that even he could not always live up to but which points the way for any person who aspires to create works that have lasting quality. It also should be instructive to those who, like Beal, have elitist notions about their compositional acumen when, in fact, they have taken a rather lackluster approach from start to finish.

By comparison with Eakins portrait of Dr. Gross, the realism that Beal proudly extols holds little interest for most of us, and his unwillingness to go beyond that, to add to that reality in any enriching way, makes his efforts seem empty, banal and pointless.

by Richard | Dec 21, 2011 | Artists' Struggles, Color Mixing, Teaching Philosophy, Uncategorized

All students who strive to create life-like portraits at some point ask me, “How do I create flesh tones?” So, when I recently had occasion to put my answer to this question in writing—having been asked it by a former student via e-mail—I thought it might make a useful blog posting. With her permission, I have posted this student’s e-mail to me (for context) and the relevant portion of my reply. As always, if you would like me to explain any of this more fully, my studio door is open to you—as is this blog.

All students who strive to create life-like portraits at some point ask me, “How do I create flesh tones?” So, when I recently had occasion to put my answer to this question in writing—having been asked it by a former student via e-mail—I thought it might make a useful blog posting. With her permission, I have posted this student’s e-mail to me (for context) and the relevant portion of my reply. As always, if you would like me to explain any of this more fully, my studio door is open to you—as is this blog.

It’s Susan Dillard. A blast from the past. Still living happily ever after in South Carolina. . . . I am writing because I’m really struggling with my flesh tone palette and I was hoping you might give me a little direction.

When I came here [to South Carolina] and beg[a]n studying with Jean Pilk, who had studied for years with Daniel Greene, [she] directed me to use a palette of Cadmium Red light with Yellow Ochre as a base. From that she would mix variations incorporating different levels of grey. I have always found this combination to be unnaturally red.

Next, I studied Sanden’s palette, which again used red light and yellow ochre but calmed it down with viridian, or chromium green, or cerulean blue. His palette variations for halftones etc are very complicated.

I did a workshop in North Carolina last year with Rich Nelson. He simply uses Burnt Sienna for flesh tones. Adding other colors too it. Whoa!

Recently I ran across a blog Marvin Mattelson whose style and color are similar t[o] the flesh tones I have seen you use in the studio (although I have never seen your palette). He has taken ALL cadmium out of his palette. His goal is to create “natural not electric skin tones.” Here is his theory,

“I was drawn to the flesh tones of William McGregor Paxton, who in my humble opinion was the greatest colorist of flesh. Paxton theorized if we come from dust and return to dust we should use dust (earth colors) when painting flesh.” He says, “it is almost impossible to paint a bad looking flesh tone if you approach it intelligently. My flesh colors are, Venetian Red, Indian Red, Yellow Ochre, Raw Umber, Ivory Black, and Flake White.”

He also uses in his palette Ultramarine Blue, Permanent Alizarin, Viridian Green also Michael Harding’s Naples Yellow and Michael Harding’s Vermillion. Plus, neutral greys.

This sounds like a great palette because I’m looking for more natural tones in my work. But I almost become frozen when I lay out a palette. Do I premix? What color are shadows? What am I doing? It’s very confusing.

Any suggestions? I have loved the colors in your portraits more than any I have seen and I would love to get your thought on flesh tone palettes or any book suggestions.

—Susan Dillard, October 9, 2011

Dear Blast from the Past,

. . . . I like what you said about Marvin Mattelson and his use of color. His palette probably is not very different from mine. Pilk has a fairly decent idea with the gray but she would have very little variation because she has only one red and that one is not versatile. Nelson’s approach sounds limiting. Sanden is very efficient, obviously with all the commission work he does, but too systematic for me with all that premixing. I do think a really fine painting with fine flesh colors can be done with Mattelson’s palette.

A few thoughts:

1. The white factor. The richness, vibrancy or saturation of a color is always diminished and made cooler by the addition of white, especially a cool white like titanium. That’s why you always have to make a completely different mix from the light area to the middle tone area to the darks. Burnt umber in the darks could be too hot but stone cold gray in the lights.

2. The transparency or opacity of a pigment has a lot to do with its quality of color and that can differ quite a lot from one pigment to the other. You have to experiment to find exactly the right kind of transparency or opacity for representing a particular color in nature, and to do that you have to put together pigments with the right combination of those things in the right proportions, i.e., if you use the translucent white flake for flesh it might be better to use a more opaque yellow like Naples and if you use a more opaque white like titanium it might be better to use a semi-translucent yellow like yellow ochre.

3. Every basic color should have a pigment on either side of it. Red should have an orange side like cad. red light, and one on the purple side like alizarin. In the earth colors the same thing: Venetian red or burnt sienna on the orange side and Indian red on the purple side. Flesh colors are difficult because they are so subtle. So the trick really is in knowing how to get yourself in the ball park, or to a general color that is close, and then to tip it this way and that, on either side of the hypothetical middle color, red or yellow or green or blue, and so on until it falls into place just where you want it. There is no way around that. No simple silver bullet.

4. Variations of the colors, sometimes beyond the perfectly real and natural, make flesh seem alive and lively. That could be just the very subtle differences in a reddish beige color that shifts slightly from a more orange type to a more purplish type. In the cool areas the same idea applies: a beige or brownish that shifts a little toward green here and blue or purplish there might do the trick. The face has natural areas that differ in color that way but you can make the lights, darks, and middles tip in different directions to accomplish that too. Between those areas you can shift the colors subtly from warms to cools to warms to cools.

—Richard Halstead, October 10, 2011

by Richard | Dec 7, 2011 | Andrew Wyeth, Artists' Struggles, N. C. Wyeth

There were three artists in the Wyeth family. The first was N.C. (Newell Convers) Wyeth, the second, Andrew Wyeth, and the third, James Wyeth who is the only one still living.

N.C. Wyeth illustration from Treasure Island

N.C. was very famous in his time and is still well known for his powerful, dramatic, operatic illustrations of adventure books and stories. His figures are heroic in proportions and always give the appearance of at least having a potential for violence. Solidly but simply constructed, they are made with little detail, yet the thick use of paint simulates the busy textures of nature, contributing to the dynamic quality of his work.

Andrew Wyeth was one of the best known artists in the country and is still well known for his quiet, austere, haunting images of people and scenes normally overlooked in the general scheme of life. (See http://www.andrewwyeth.com/index.html) His paintings are contemplative and they often have a sense of timelessness which is alternately unsettling and comforting. This effect was accomplished by a delicate balance between highly rendered details and compositional simplicity and by using form as means of creating subtle lighting effects that in turn created their special moods.

N.C. died with his grandson in a car-train accident. There has been speculation that the death was suicide possibly because of a bi-polar condition and ongoing angst over his unfulfilled attempts at bringing his work to a higher level.

Andrew Wyeth seemed to pity his father’s loss of faith in his own natural talents and for his attempts at creating work that was opposite that nature. But Ironically Andrew made the same mistake in reverse. N.C. dismissed the unique power in his dramatic illustrations and tried to create work that expressed the infinite and universal in the small and mundane aspects of life. In a similar manner Andrew gave less credence to the quiet timelessness in his paintings and more to a powerful force that he preferred to believe was emanating from them.

I think both men were more honest with themselves when they were young than when they were in their later years—truer to themselves before they began to judge themselves against all they admired in life, and in each other.

When N.C. was a young illustrator and doing research for illustrations on the western plains of the U.S. he wrote home about how life there “clutches me like some unseen animal.” Later in his life he wrote “The significance of a tiny speck of bark on the pine tree assumes the proportions of the infinite sky”—words that better describe his son’s work than his own.

Andrew said, by way of describing Rembrandt’s paintings, “His people turn toward the light. but it’s frozen motion; time is holding its breath for an instant—for an eternity. That’s what I’m after.” But later, when the quality of his work had declined he spoke as if his paintings were charged with heightened emotions, using words like anger and intensity, which better describe his father’s work.

The loss of self is not unusual among artists. A consciousness of self expression is a relatively new requirement in the history of art and is, I think, one of the primary difficulties for artists today. Until the19th century it was a secondary concern. Finding one’s self and creating an effective means of expression that meets the present sense of art’s function is often a mirage-like experience. The more deliberate we are about it the more it seems to slip away form us. That is the most difficult lesson to learn in creating art and the most difficult puzzle to solve.