The Wyndham Sisters by John Singer Sargent

Considering how many books and articles have been devoted to John Singer Sargent’s life and paintings, there is surprisingly little written that attempts to explain the phenomenon of his paintings. Even artists who emulate his style generally see them as the works of a transcendent mind that can never be understood through analyses. For many of the students and followers of Sargent, the spontaneity within his paintings is the essence of that transcendent mind. Consequently, the principle they tend to apply when viewing his work, or in making their own paintings, is “Don’t think too much.”

He did fill his paintings with spontaneous passages, as a jazz musician might, and after a brief time early in his career it seems that he went directly into his paintings without any significant compositional studies. Nevertheless, there is a conscious mind behind those flashes of genius, judging, selecting and organizing them into a cohesive whole. Sargent was said to have frequently scraped down, rubbed out and reworked various areas to get the effects that he wanted. The combination of letting things fall as they may and of reconsidering or editing from those moments is what made his paintings great works of art.

Sargent had a special advantage over other artists in that he could think at an extraordinary speed. That may seem like an insignificant detail, but in a direct painting style an artist has to make important decisions within the limited time he has before the paint dries, just as a musician’s mind has to work at the speed or tempo of the piece he is performing. Sargent had a quick and agile mind, and one that could think throughout that drying time toward a final and complete orchestration.

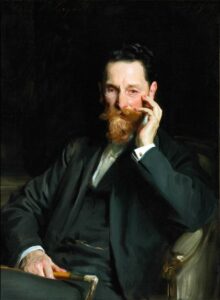

To have a basic understanding of Sargent’s creative process, a person needs to consider what Sargent was not. He was not an artist consumed with interest in the subject’s character, so he was not distracted by it. While he was painting a portrait of the publisher Joseph Pulitzer, he actually stated that he was not interested in character, saying, “Sometimes I get a good likeness—so much the better for both of us. Sometimes I don’t—so much the worse for the subject, but I make no attempt to represent anything but what the outward appearance of a man or woman indicates.”

He was more interested in the ballet of the figures moving about in the illusionary worlds he created on canvases and in the visual music of his compositions and brushwork. Essentially, he was consumed by the creation of beauty, and he seems to have had no need to “say” anything beyond that. His clients must have sensed this fact even if they didn’t understand it. In their day, his portraits were recognized as elegantly modern images in which people wanted their likenesses placed, even if that likeness was vague.

I believe the best way to understand Sargent’s work is to see in his paintings parallels to music. Music is a timeline form of art (art that moves in time) in which the lyrics, if they are used, are carried by the rhythm, melody and spacing of time within it. Painting is a static form of art, but we view it in a timeline manner, according to where and in what priority our attention lands in different parts of the composition and pictorial space. In a good painting, our attention is guided by principles very much like the rhythm, melody and spacing in music. All representational or realistic paintings, if they are successful, are carried by these elements, described generally as design or composition, or as an underlying abstraction.

The realism in these paintings can be equated to the lyrics in a song in that both refer to ideas (often described as programmatic in music). In representational art, as in music with lyrics, there is always a balance between a reference to ideas, or meaning, and the composition or design that carries that meaning. Generally, however, one side of the equation is more dominant than the other.

In Sargent’s paintings, the realism is of an extremely high order, but the design (the shapes, texture, color, brushwork, form, and movement) predominates in the way it carries that realism. Music lovers talk about being swept away by a particular piece of music and that is very much like what happens to those of us who love Sargent’s work. The abstract side of his paintings moves us with the conspicuous excitement and grace of his execution and the unique patterns of his compositions.

But even with that predominance of abstract design, the realism is strengthened by it because it contributes largely to the feeling of life and liveliness of the figures. Sargent’s paintings are grounded in traditional realism, as dancers in a performance are grounded by the stage beneath them, reminding us that they are real people. Sargent’s paintings are firmly planted in the here and now, but the beauty of his performance, as with ballet or opera, is what moves us and elevates us out of the stresses of our daily routines.

So I was not surprised when I learned that Sargent was an accomplished musician as well as a painter. Percy Grainger and Gabriel Fauré, famous musicians and close friends of Sargent’s, said of him that his musical ability was as great as his painting skills. It is apparent, therefore, that either music had a profound influence on the way he painted and the way he thought about painting, or, music and painting were just two aspects of the same thing for him. I’m inclined to believe the latter.

My friend, the French-horn player Lisa Taylor, wrote to me recently describing Sargent’s paintings as having, “a richness, joy, lyricism and mastery of rapturous melodic line and harmony.” She compared them to compositions by the musical impressionists Fauré, Ravel, and Debussy and to the works of Shubert, Dvorak, Mozart, and Brahms, whose compositions she described as “sound tapestries of different textures and colors, created by composers who brought out the best of each instrument for which they composed.”

Others have compared his work to jazz greats. Gerald Lazare, an artist friend and honorary member of the Duke Ellington Society of Canada, sees parallels between Sargent’s paintings and Ellington’s compositions, which combine the improvisations of jazz with formal composition. He compares the dramatic range of extreme lights to extreme darks in Sargent’s paintings with Ellington’s way of using a range of sounds from the highest clarinet to the lowest baritone sax.

Paul Helleu Sketching with His Wife by John Singer Sargent

People often compare Sargent to the artists Velasquez and Franz Hals because of the looseness and dash of their brushstrokes. The brushwork of these great artists, each in its way, is powerful and timeless in its expression, but neither artist’s work has the flowing musical quality that exists in Sargent’s paintings. I associate him more with painters of the late Renaissance and Baroque periods in Italy, especially those in Venice, which was once known as the Republic of Music. The paintings of Veronese, for example, are composed as if they are rolling with elegant song and celebration; Guardi’s brushstrokes are like clear, decisive rings from brass and reed; Tiepolo’s paintings are grand opera at its best; and Tintoretto’s have the energy and intensity of some of the symphonic music of the Romantic period.

To see the musicality in Sargent’s paintings is to expand our experience of them and to understand ourselves better in the course of doing that. The first reaction most of us have to his work is awe. We feel a vicarious thrill in the power and assuredness of his athletic prowess as an artist. Then the music reaches us, independent of the performer and composer, and a door to pure exaltation opens to us. We become aware of that combination of classical order and pure, innocent joy. Many years ago, I saw on the back of an LP album cover a description of the Venetian composer Vivaldi that read, “Entirely serious in his joyfulness.” Could there possibly be a better tribute to the art and creative life of John Singer Sargent?